The Tudor period is fascinating for many reasons, not least because there is such a wealth of published secondary sources around now that it is relatively easy to find information about even fairly obscure individuals. I was recently asked by a client to research a distant ancestor who had died in Sussex in 1541. In the course of my searches I discovered a web of interconnected families in Sussex, Hampshire, Northamptonshire and beyond, all with links to the legal profession and the Inns of Court.1

The names of Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas More came up – two prominent victims of Henry VIII’s quest to ditch wife number one, Katherine of Aragon, for wife number two, Anne Boleyn. How exciting was that?

Some of these families had started as prosperous yeomen and had managed to build up land holdings and enough wealth to send their sons to be educated at the Inns of Court in London. The Inns of Court have been described as the ‘third university’ in England at this period, after Oxford and Cambridge, and their copious records are still preserved in the various archives of the Inns.

These have long been an invaluable resource for researching members of the legal profession but only a portion of their collections has ever been digitised and available online, so looking for individual lawyers in the late medieval or early modern period is still a daunting prospect.

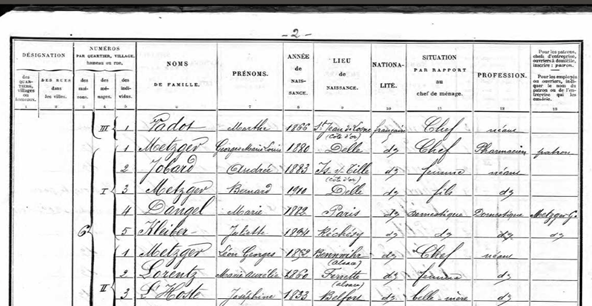

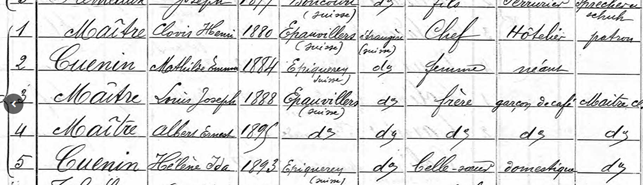

Fortunately a dedicated team of academic researchers realised this and spent over 30 years working on the problem. In 2012 they produced the huge, two volume biographical reference book, compiled by John Baker, The Men of Court 1440-1550: A Prosopography of the Inns of Court and Chancery and the Courts of Law.2 This might not be the sexiest title you’ve ever come across, but I assure you, if late medieval and Tudor lawyers are your bag you’re in for a real treat!

It is no less than an attempt to produce a brief biography, based on a wealth of sources, including wills and land records, of every person connected with the law during this time. Each entry includes the person’s significant dates (where known) and provides cross references to the entries of others named in the work. Speaking as someone who started out in reference publishing, I salute their heroic endeavour!

For anyone lucky enough to find an entry for the person they are looking for there are vital document references to support all the information given. One of the other marvellous things about The Men of Court, whether you are researching someone connected with the law or not, are the lists of sources. These are especially useful if you don’t happen to have an encyclopaedic knowledge of exactly what records are available for this period. For example in volume 1 there is a one page list, broken down by county, of the main transcribed and published collections of English Tudor taxation records.

In my case, I discovered that the man I was researching had belonged to the Middle Temple.3 Knowing which of the Inns of Court a lawyer belonged to is important for tracking down further information on them and not every Inn has so far digitised their membership registers, or made this available online. So an entry in Baker can save a lot of legwork.

My client and I knew how Cardinal Thomas Wolsey fitted into his ancestor’s life story but we had been scratching our heads trying to work out how ‘our man’ knew the famous martyr and London lawyer, Sir Thomas More. It wasn’t entirely clear how their professional lives would have intersected. Again, Baker came to the rescue because I found out that there was more than one Thomas More operating as a lawyer in London at this period, which possibly meant there was no connection to the famous Thomas More after all. What a disappointment!

But Baker more than made up for this depressing discovery by then revealing that one of the Thomas Mores just happened to be the treasurer of the Middle Temple around the time our man was admitted. Not only was this Thomas More from the same geographical area as my client’s ancestor, making him a more likely match, but he (Thomas More) was probably instrumental in facilitating the ancestor’s admission to the Middle Temple in the first place.

Amusingly enough I then discovered that if I’d really had my wits about me I would have first consulted volume 4 (Number 13), Issue 1, February 1967 of the journal Moreana published by Edinburgh University Press, where an article by E. E. Reynolds, entitled ‘Which Thomas More? A Retractation’ described making exactly the same mistake and warned others to always check their sources – a nagging voice familiar to all researchers.

As if to illustrate this, it turns out that even a superlative secondary source like Baker can’t always be relied on for 100% accuracy. The entry for the son and heir of the client’s ancestor suggested he was born in ‘November 1520’, giving as evidence a National Archives (TNA) document reference for his father’s inquisition post mortem.4 But I knew that this Latin document in TNA could not support such a birth date because I had seen the original, and I had already transcribed and translated its nearly exact copy, from a companion collection in TNA. Using my translation I worked out that the son’s birth date was in fact 23 July 1531.

Given the enormous scope of a monumental work like The Men of Court, I think we can excuse Baker for the odd error creeping in, but – like the man said – there’s no substitute for doing your own research!

- The Inns of Court, located near the Royal Courts of Justice in London, are four institutions dating to medieval times that have been historically responsible for legal education. They are: Inner Temple, Middle Temple, Lincoln’s Inn and Gray’s Inn. ↩︎

- Baker, J. (2012) The men of court 1440-1550 : a prosopography of the Inns of Court and Chancery and the Courts of Law. London: Selden Society. ↩︎

- The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, along with the Inner Temple, has its origins in the order of the Knights Templar, who completed and consecrated the Temple Church, as it is known today, in 1185. Thereafter a substantial complex of buildings grew up around it. ↩︎

- These were local inquiries undertaken on the death of holders of crown lands “in order to discover what income and rights were due to the crown and who the heir should be.” ↩︎