The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.

L P Hartley

On Sunday 1 August 1914, a 56 year old English businessman hurried from his accommodation in Rixheim, a suburb of Mülhausen in Alsace, toting a heavy case and in search of transport home. He was in the middle of a business trip and had been monitoring the worsening political situation in Europe for several days, during which time ‘letters to England were returned to us, no telegrams were permitted, and the local telephone was disconnected’. By Sunday he had resolved to leave. If he’d delayed, he would have found himself in the middle of one of the first engagements of the First World War on the Western Front: the Battle of Mülhausen.

I found a contemporary newspaper account of this intrepid Edwardian’s dramatic journey back to Blighty in a microfilm collection at Hertfordshire Archives and Local History Studies (HALS). The British Newspaper Archive (BNA), while being a truly wonderful resource, doesn’t have every newspaper, and for some titles it only has copies from certain years in their collection. It’s always worth checking in your local county archives to see if they have newspapers not covered by the BNA. After some further research online I was able to discover quite a lot more about this gentleman’s life and his connection to Alsace, which helped explain what he was doing there in the first place. I’m planning to explore this in a future post, or possibly an article.

Intrigued by his story, I was keen to learn more about Alsace, with its history of shifting borders and a population regularly rendered ‘foreign’ at a stroke. So I thought I’d take a look at census returns from this area for the period just before the outbreak of the 1914-18 war.

The 2021 census of all parts of the United Kingdom took place on 21 March. The 100-year time limit for the release of records from the 1921 census is also nearly upon us. From 6 January 2022 historians, genealogists, and family history enthusiasts will be able to consult the records from England and Wales on Findmypast.

The information recorded by early censuses in the UK was limited – for example the 1801 census was mainly concerned with gathering regional and national data on the number and size of households across the country – and the details were not considered important, most being destroyed. The sorts of questions posed in the census can in themselves be revealing insights into society at the time, as no doubt will be the questions in the 2021 census. All of this provides fascinating grist to the mill of historians.

Borderland

If, according to L P Hartley’s 1953 novel, The Go-between, the past is virtually a foreign country, how much more ‘foreign’ might the past of a completely different country be? France began conducting national censuses (recensements) every five years from 1801 and I thought it would be interesting to look at returns from the 1911 one, since this is also the latest year for which historic UK census records are currently available.

The commune of Delle, in the département of the Haut Rhin in eastern France, came under the administrative territory of Belfort, which had historically been part of Alsace. The 1870 treaty which ended the Franco-Prussian war saw Belfort carved out of Alsace to remain in France, while the rest of the region was subsumed into the German Empire. Maps of the period show Delle in its French enclave, bordered by the rest of Alsace on one side and Switzerland on another.

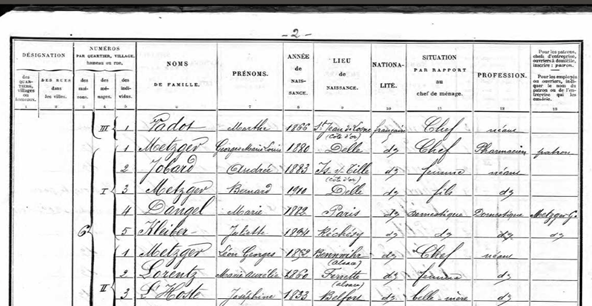

According to the census of that year, Delle’s population in 1911 amounted to 2627 individuals. A quick glance at the records reveals an interesting aspect of the French census which differs from the UK censuses of the period: married women were listed by their maiden names, not their married names. In the example below we see that the wife of farmer Célestin Schmitt is Marie Daucours.

That sort of detail could be gold dust to a family historian and might help, along with Marie’s recorded year of birth (année de naissance) and birthplace (lieu de naissance), to locate a marriage record for the couple and an earlier birth record for Marie. However, as most family researchers know, life isn’t always straightforward and in practice it’s often difficult to find records in archives if the information hasn’t been name indexed or, even better, digitized. Marie was born in Switzerland and unfortunately only some Swiss births, marriages, and deaths records (otherwise known as BMD) are available online; FamilySearch and Ancestry have some collections but they are incomplete.

By contrast, online BMD collections for England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland are far more complete; but locating a married woman in a 1911 UK census return wouldn’t necessarily make it easy to find other records for her, because only her married name would be recorded in the census. So to uncover her maiden name might involve quite a lot of frustrating extra work.

In general, however, the treatment of married women in the censuses of both countries at this time is similar: they imply that, by definition, they didn’t do anything worth noting. Under the heading profession in the French census the word néant (meaning none) was recorded for the majority of married or widowed women, as it is for Marie Daucours above. In the UK censuses this column was commonly just left blank for married women. This is a classic example of how a census can reveal something about the society performing it even when it leaves things out!

In the Delle census of 1911 there are some intriguing exceptions to this rule. Marie Weber, the 38-year-old wife of locksmith Charles Jacob, is recorded as running her own grocery and haberdashery business. The last column in the census form was where the enumerator noted details of a person’s employer. The words patron for a man or, less commonly, patronne for a woman, indicated that the person owned their own business.

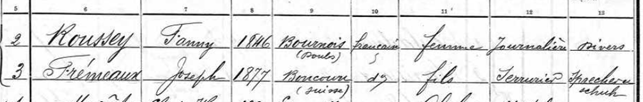

Further down the page we find Fanny Roussey, the 66-year-old wife of François Frémeaux. François is a few years older than Fanny and has no recorded occupation, but she works as a day labourer (journalière), probably doing manual work of some kind.

The mention divers in column thirteen means that Fanny works for more than one employer, possibly local farmers. To be engaged in that kind of hard, physical work at her age, Fanny is what the French might call une femme courageuse!

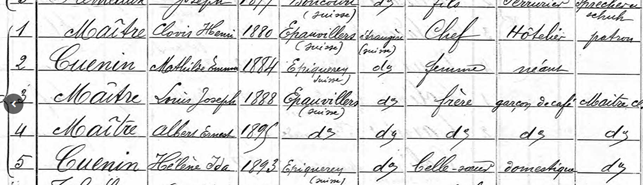

In some cases, it’s easy to estimate what a married woman was actually doing from the context of the household. For example, the Delle census return lists Mathilde Emma Cuenin, wife of the wonderfully-named Swiss hotelier Clovis Henri Maître. Although Mathilde’s occupation is recorded as néant, she was very probably closely involved in running the hotel, given that it employed her sister as a maid and her husband’s two brothers as waiters. On the other hand, it’s just possible that she sat around all day eating Swiss chocolates while the rest of the family busied themselves with useful tasks. We’ll never know.

From this cursory look at the census returns we start to get a picture – however hazy – of the population of Delle in the period just before the First World War. So far, we can deduce that it had enough agriculture to support jobbing labourers and was large enough for small businesses to establish themselves – and that it had at least one hotel. Some of the population appear to have been born over the border in Switzerland.

In my next post I’ll continue to explore records from Delle to try to flesh out this sketch.