My recent post on Herts Memories, Hertfordshire’s community archive network hosted by Hertfordshire Archives and Local History (HALS).

Category: Railways

At the frontiers of tourism

On 17 September 1888 the Pall Mall Gazette of London declared: ‘ “Boycott Mulhausen and take up with Delle” should be the tourists’ Plan of Campaign’. This surprising rallying cry had been sparked by a recent unfortunate incident at Mülhausen (known as Mulhouse in French) on the Alsace-Swiss border.

Charles Seale Hayne, Liberal MP for Ashburton in Devon, had chosen to travel from Belfort, just north of Delle, on the German Imperial Railways in Alsace Lorraine, via Mülhausen to Basle in Switzerland. The problem was he didn’t have a passport. The Gazette explained that because of the recently introduced ‘vexatious passport regulations’ in Alsace, he was refused entry and detained at Mülhausen by German authorities. Expressing scant sympathy for Mr Seale Hayne, the Gazette remarked that it had been ‘pointed out over and over again for the benefit of English tourists that there were two lines from Belfort to Basle, one of which does, and the other of which does not, pass through German territory … he ought to have gone by the Franco-Swiss one’. They went on to note acidly that, in the matter of coming a cropper when you’ve broken the rules, ‘Members of Parliament must not expect to be safer than other individuals’. How topical that sounds!

Alsace and Lorraine had been French but were ceded to Germany at the end of the Franco–Prussian war in 1871. Since then they had been a flashpoint in an escalating war of nerves between the two countries, which was punctuated by periodic outbursts of megaphone diplomacy. The new ‘vexatious’ passport rules were the latest act in this long-running drama. Germany was experiencing some domestic drama at the time as well: a few days after the new passport rules came into force, on 1 June 1888, it acquired a new Emperor – Kaiser Wilhelm Ⅱ.

The regulations in question proclaimed that any foreigner entering Alsace–Lorraine from France required a passport, with accompanying visa from the German embassy. For those wishing to travel to Basle there was an alternative route via the French railway company, La Compagnie des Chemins de fer de l’Est, which avoided crossing into German territory and didn’t need a passport. This explains the Pall Mall Gazette‘s sensible advice to tourists.

Passports were something of a novelty at this period. In fact, as the UK National Archives’ study guide points out, ‘[b]efore the First World War it was not compulsory for someone travelling abroad to apply for a passport. Possession of a passport was confined largely to merchants and diplomats, and the vast majority of those travelling overseas had no formal documents’. So these new rules represented a significant, and expensive, inconvenience for anyone wishing to travel through France into Alsace–Lorraine.

By the middle of the 19th century there were increasing numbers of British tourists keen to explore Alsace, especially the Vosges mountains which attracted exponents of the relatively new pastime of mountain climbing, or alpinism as it was known. Initially mountaineering was the preserve of the English upper class, who had been pioneers of this gentlemanly sport. In 1865 a group of young climbers, including three Englishmen, became the first to reach the summit of the Matterhorn in Switzerland. Tragically, they became even more famous for the controversial accident on their descent which killed several of the party, including Lord Francis Douglas. By the close of the century the monied middle classes were also venturing into the mountains in greater numbers and local hotels and restaurants were quick to capitalize on the growth in foreign tourism.

As well as being a trying inconvenience for prosperous tourists, the passport regulations threatened to make daily life for ordinary frontaliers – those who lived and worked in the border area between France and Alsace – a source of constant aggravation. There was much bad press in France and Britain about the heavy-handedness of German passport officials. The Yorkshire Evening Press of 5 June 1888 repeated a French newspaper report that German authorities had prevented some French army veterans who lived in Alsace from returning home after their regular trips across the border to France to receive their pension payments.

But there are hints that in practice the regulations quickly became honoured more in the breach than in the observance. The St James’s Gazette of 1 October 1890 featured an account of two British tourists ‘bent on a tramp among the hills of Alsace’. Having duly armed themselves with the required visas from the German embassy in London, they found that they didn’t need them once during their ten-day excursion, even though they had crossed and re-crossed the France–Alsace border many times. In fact they each greatly regretted the ten shillings they had shelled out for their visas. To encourage fellow tourists to consider sampling the delights of ‘this truly beautiful holiday-ground’ the writer helpfully detailed the sort of typical, mouth-watering lunch that travellers could expect at a local Alsatian inn: ‘excellent soup, iced salmon with mayonnaise sauce, fillet of beef with potatoes … veal cooked as only foreigners can cook it, with meringues and cream and cheese to follow’. All for less than four shillings apiece, including a bottle of ‘fair’ wine. It’s hard to imagine anyone tramping much further than their hotel room for une sieste after consuming that meal!

Eventually the difficulties for locals and tourists alike, not to mention political pressure, led to the passport regulations being officially revoked on 1 October 1891. But the experience had helped to keep alive the question of Alsace and Lorraine’s status as German territories and there were increasing calls for their restoration to France. The issue was by no means straightforward. By the late 1890s nearly 30 years had passed since these areas had become part of the German Empire and a new generation had grown up knowing nothing else. In 1898 a British newspaper reported the impressions of another tourist, recently returned from a ‘long holiday sojourn in Alsace and Lorraine’. He was convinced that most of the younger population were quite happy with their lot and observed that nothing ‘a succession of French Governments have done since 1871, including their dealings with Dreyfus, is calculated to inspire the Lorraine breast with a desire to be again under its control’.

The reference to the Dreyfus affair was very topical and it had local significance for Alsatians. Alfred Dreyfus had been born into a Jewish family in Mulhouse in 1859, before the area was ceded to Germany and became known as Mülhausen. He had subsequently become a cavalry officer in the French army and was wrongly convicted of spying for the German Empire by a secret court martial in 1895, then sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island in French Guiana. His case became an international cause célèbre. Emile Zola famously addressed his open letter to the President of the French Republic in defence of Dreyfus, J’accuse, in which he denounced the military establishment as anti-Semitic. Alfred Dreyfus had to wait until 1906 before being completely exonerated. The actual spy was later revealed to be Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy who escaped to Britain and died in Harpenden in Hertfordshire in 1923.

Some of this turmoil and paranoia about spies and foreigners can be detected in the French censuses. Up to 1881 they did not record the nationality of householders, but from 1886 onwards they did. For residents of a town like Delle – next to the borders with Switzerland and the rest of Alsace – this emphasis on stating your nationality might have felt vaguely threatening, especially as many of them had probably been born in parts of Alsace now in the German Empire. For historians and family researchers, however, it could offer some insight into how diverse the population was.

The census data from Delle between 1886 and 1911 record a steady increase in the number of households and persons enumerated although, curiously, the number of households seemed to increase at a faster rate than the number of inhabited buildings. This was especially so between 1891 and 1896. Could this mean that there was a shortage of housing? It would be interesting to discover if this was because of particular local conditions or if it simply mirrored a national trend.

I’ll explore more records from Delle in my next post.

What did they do?

From 1836 to 1936, barring during wartime, France conducted national censuses every five years. These can be consulted in person in regional and local archives in France, but unfortunately few of them have been indexed or digitized so not many are available to see online. FamilySearch has indexed some of these for some years, and they also have some record images, but the coverage is very patchy. The exception is the territory of Belfort, in the Haut Rhin département in Alsace: Ancestry has nearly all of these available to view in its collection Belfort, Alsace, France, Censuses 1836-1911. However, you do need to have an international Ancestry subscription to access them, which isn’t cheap. Luckily this is also one of the few census collections in France that is available to view for free online at the website of the local archives.

What’s more, this free resource covers the entire period from 1836 to 1936, so is more complete than the Ancestry collection.

In my previous post I looked at the 1911 census of Delle, which is in the Belfort territory, and we saw that the final two columns on the census form were for recording occupation and name of employer. According to FindMyPast, the 1921 census of England and Wales, soon to be available to their subscribers, also contained this information. It could prove quite useful in locating potential employment records for someone.

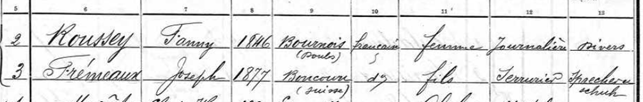

For example in the Frémeaux family we saw earlier, Joseph Frémeaux, the adult son, is recorded as locksmith and his employer is noted as Sprecher et Schuh.

Further investigation reveals that Sprecher & Schuh is a company still operating in Switzerland, which manufactures industrial control products – electrical switches to you and me. Joseph appears to be what is known in French as a frontalier: someone who lives in one country and commutes across the border to work in a neighbouring country. Sprecher & Schuh features in the census entries of quite a few other Delle residents, suggesting the company may have been a significant employer in the region. It’s possible that the archives of Sprecher & Schuh contain historic staff records which might provide a family researcher with valuable information on an ancestor.

We are sometimes stumped by the terminology used to describe occupations in historic documents, especially if they’ve been obsolete for some time due to changes in technology, such as clay burner or railway platelayer. Old trades directories can also sometimes be baffling for the same reason. My eye was once caught by a particularly striking category listed in a 19th century London commercial directory: scum boilers. That definitely sounds like a contender for the prize of The Worst Job In History! Only one unfortunate soul was prepared to advertise his skills in this area, so it looks like he enjoyed a monopoly!

For English speakers, French censuses introduce an extra level of complexity; but fortunately it is possible to find translations of common French job titles, like the useful alphabetical list provided by Family Search. There is also a handy glossary of French genealogical terms on The French Genealogy Blog. This website, in English, is an indispensable resource for anyone hoping to negotiate the complexities of French records and where to find them.

However, the first hurdle is usually trying to decipher French handwriting – not an easy task if you’re unfamiliar with it. Even today many French people write with a distinctive, cursive script which was drummed into them from an early age at school. It’s pretty to look at but often very hard to read if you’re not used to it, which makes trying to interpret handwritten documents particularly challenging. I have a couple of tips. Watch out for lower case ‘r’ in the middle of a word – it’s sometimes easy to confuse these with an ‘n’. Also, upper case ‘S’ can look like ‘J’. For example, look at the word in column 12 of Joseph Frémeaux’s entry above: it’s Serrurier (locksmith). Notice all those ‘r’s!

In spite of its size, Delle’s location next to two international borders, and served by a busy rail network, must have given it a bustling, dynamic air. We get some idea of the daily movements of passengers from the wonderful Bradshaw’s Continental Railway Guide, published in 1913.

At this period Swiss Railways ran trains between Belfort and Basle, stopping at Delle regularly throughout the day until about 9pm. This would have been used by many frontaliers for their daily commute. Swiss Railways also laid on extra trains during the summer holiday period, from the beginning of July till mid-September, so Delle may have seen a lot of holiday traffic too. Travellers from London could even map their route to Basle, with the aid of Bradshaw’s handy Direct Through Tables. Leaving Victoria at 11am, they would find themselves passing through Delle at 5am the next morning on their way to Basle.

It has often been remarked that the First World War could not have happened without the European rail network, criss-crossing the continent and enabling troops and munitions to be mobilised rapidly. Delle residents would soon learn first hand just how uncomfortable their key position could make things for them.

Looking again at the French 1911 census, in particular the instructions to enumerators in the preamble, it becomes clear that only those who were normally resident in the area were to be included, irrespective of whether they were present or not on the day of the census. Anyone researching UK census records will be familiar with the sense of frustration when you discover that a certain individual was unaccountably absent from the family home on the night of the census. This frequently necessitates long and often fruitless searches for the person elsewhere. In France it seems, a person’s inclusion in the census doesn’t necessarily mean they were at home when the census enumerator called.

In one way this is useful, because it means someone is less likely to be missed because they were, say, visiting relatives or on holiday. But in another way the UK census method, while occasionally misplacing people for ten years, can give a fascinating glimpse into what they were actually doing when they were away from home. For example it can sometimes reveal family interconnectedness which would otherwise have remained hidden, as in the case of a child staying with relatives with a different surname.

In the French system, enumerators were instructed to keep three lists: one for those who were normally resident and present on the day of the census; one for those who were normally resident, but were temporarily absent; and a separate list for visitors to the household who were en passant. I don’t know whether these lists were preserved but if they were, having access to them might prove very useful for researching ‘missing’ French ancestors. In France, as in Britain, soldiers, sailors, prisoners and children at boarding school were enumerated separately, not in their homes.