From 1836 to 1936, barring during wartime, France conducted national censuses every five years. These can be consulted in person in regional and local archives in France, but unfortunately few of them have been indexed or digitized so not many are available to see online. FamilySearch has indexed some of these for some years, and they also have some record images, but the coverage is very patchy. The exception is the territory of Belfort, in the Haut Rhin département in Alsace: Ancestry has nearly all of these available to view in its collection Belfort, Alsace, France, Censuses 1836-1911. However, you do need to have an international Ancestry subscription to access them, which isn’t cheap. Luckily this is also one of the few census collections in France that is available to view for free online at the website of the local archives.

What’s more, this free resource covers the entire period from 1836 to 1936, so is more complete than the Ancestry collection.

In my previous post I looked at the 1911 census of Delle, which is in the Belfort territory, and we saw that the final two columns on the census form were for recording occupation and name of employer. According to FindMyPast, the 1921 census of England and Wales, soon to be available to their subscribers, also contained this information. It could prove quite useful in locating potential employment records for someone.

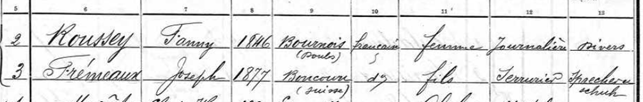

For example in the Frémeaux family we saw earlier, Joseph Frémeaux, the adult son, is recorded as locksmith and his employer is noted as Sprecher et Schuh.

Further investigation reveals that Sprecher & Schuh is a company still operating in Switzerland, which manufactures industrial control products – electrical switches to you and me. Joseph appears to be what is known in French as a frontalier: someone who lives in one country and commutes across the border to work in a neighbouring country. Sprecher & Schuh features in the census entries of quite a few other Delle residents, suggesting the company may have been a significant employer in the region. It’s possible that the archives of Sprecher & Schuh contain historic staff records which might provide a family researcher with valuable information on an ancestor.

We are sometimes stumped by the terminology used to describe occupations in historic documents, especially if they’ve been obsolete for some time due to changes in technology, such as clay burner or railway platelayer. Old trades directories can also sometimes be baffling for the same reason. My eye was once caught by a particularly striking category listed in a 19th century London commercial directory: scum boilers. That definitely sounds like a contender for the prize of The Worst Job In History! Only one unfortunate soul was prepared to advertise his skills in this area, so it looks like he enjoyed a monopoly!

For English speakers, French censuses introduce an extra level of complexity; but fortunately it is possible to find translations of common French job titles, like the useful alphabetical list provided by Family Search. There is also a handy glossary of French genealogical terms on The French Genealogy Blog. This website, in English, is an indispensable resource for anyone hoping to negotiate the complexities of French records and where to find them.

However, the first hurdle is usually trying to decipher French handwriting – not an easy task if you’re unfamiliar with it. Even today many French people write with a distinctive, cursive script which was drummed into them from an early age at school. It’s pretty to look at but often very hard to read if you’re not used to it, which makes trying to interpret handwritten documents particularly challenging. I have a couple of tips. Watch out for lower case ‘r’ in the middle of a word – it’s sometimes easy to confuse these with an ‘n’. Also, upper case ‘S’ can look like ‘J’. For example, look at the word in column 12 of Joseph Frémeaux’s entry above: it’s Serrurier (locksmith). Notice all those ‘r’s!

In spite of its size, Delle’s location next to two international borders, and served by a busy rail network, must have given it a bustling, dynamic air. We get some idea of the daily movements of passengers from the wonderful Bradshaw’s Continental Railway Guide, published in 1913.

At this period Swiss Railways ran trains between Belfort and Basle, stopping at Delle regularly throughout the day until about 9pm. This would have been used by many frontaliers for their daily commute. Swiss Railways also laid on extra trains during the summer holiday period, from the beginning of July till mid-September, so Delle may have seen a lot of holiday traffic too. Travellers from London could even map their route to Basle, with the aid of Bradshaw’s handy Direct Through Tables. Leaving Victoria at 11am, they would find themselves passing through Delle at 5am the next morning on their way to Basle.

It has often been remarked that the First World War could not have happened without the European rail network, criss-crossing the continent and enabling troops and munitions to be mobilised rapidly. Delle residents would soon learn first hand just how uncomfortable their key position could make things for them.

Looking again at the French 1911 census, in particular the instructions to enumerators in the preamble, it becomes clear that only those who were normally resident in the area were to be included, irrespective of whether they were present or not on the day of the census. Anyone researching UK census records will be familiar with the sense of frustration when you discover that a certain individual was unaccountably absent from the family home on the night of the census. This frequently necessitates long and often fruitless searches for the person elsewhere. In France it seems, a person’s inclusion in the census doesn’t necessarily mean they were at home when the census enumerator called.

In one way this is useful, because it means someone is less likely to be missed because they were, say, visiting relatives or on holiday. But in another way the UK census method, while occasionally misplacing people for ten years, can give a fascinating glimpse into what they were actually doing when they were away from home. For example it can sometimes reveal family interconnectedness which would otherwise have remained hidden, as in the case of a child staying with relatives with a different surname.

In the French system, enumerators were instructed to keep three lists: one for those who were normally resident and present on the day of the census; one for those who were normally resident, but were temporarily absent; and a separate list for visitors to the household who were en passant. I don’t know whether these lists were preserved but if they were, having access to them might prove very useful for researching ‘missing’ French ancestors. In France, as in Britain, soldiers, sailors, prisoners and children at boarding school were enumerated separately, not in their homes.